Teaching history is not about filling students’ brains with knowledge. It’s about getting them to think like a historian. Using inquiry-based lesson plans in social studies classes will do just that!

How do historians think, you ask? Much like a detective at a crime scene. A detective gathers evidence, clues, and interviews from multiple sources. They evaluate the reliability of witness testimony and interrogate each point of view for bias and trustworthiness. They compare accounts to determine where stories converge and where they diverge. Then, they synthesize the evidence to construct a narrative of the crime.

Like the detective, historians use primary source documents as evidence to help them develop evidence-based arguments about the past. When students engage with inquiry-based lessons they do the work of a historian! History becomes something they do.

Inquiry-Based Lessons: A Skills-Based Approach To Teaching History

If I’m being honest, I struggled as a teacher during my first, second, and probably third year. This was not for a lack of trying. In fact, I was (and still am) very passionate about education and the impact teachers can have on young minds. To put it bluntly, my graduate program failed to teach me how to teach history and my most recent example of instruction came from the collegiate level where undergraduates marvel at the “brilliance” of their professors’ lectures. So, absent an understanding of pedagogical methods, my teaching methods were driven by lectures, notes, and a frenzied sprint to cover everything in my 1000-page history textbook by the end of the year. For my students, learning history was limited to memorizing. It was a painfully boring experience for all of us.

In my 4th year of teaching, I was assigned to teach AP U.S. History. When I started teaching AP U.S. History, I was introduced to skills-based instructional methods that focused on developing students historical thinking skills. This completely changed my teaching approach to both Advanced Placement and core US History classes. During this time, I began to adopt what many consider the gold-standard of skills-based historical pedagogy: the inquiry-based lesson.

Like the more familiar Document-Based Question (DBQ), inquiry-based lessons requires students to analyze a range of primary source documents to develop a reasoned argument that is supported with evidence. Whereas DBQs often take place in one class period (and often as an independent assessment), inquiry-based lessons take place across several lessons and invites student to discuss and deliberate.

Over the decade, the inquiry-based instructional approach has gained popularity. You can read more about the key elements that make up an inquiry-based lesson here.

Why is inquiry-based instruction important for teaching social studies?

Students often ask why do we need to learn history? There are a myriad of ways to answer this question, and they mostly can be categorized into two reasons.

Reason 1: Students need to learn about the past

I agree with the notion that students need to understand history so they can understand the present. As the old saying goes, those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it. However, in my experience, dedicating 100% of my class towards learning content was not sustainable. I didn’t feel effective as a teacher, and the majority of my students didn’t find my class enjoyable. After several years in this rut, I had to find another reason to teach.

Reason 2: Students need to develop skills.

Focusing on skills instead of content helped me feel like I was making a difference in my student’s lives. Enter Inquiry-based learning. Inquiry-based teaching gave me an opportunity to engage students in critical thinking, develop reading and writing skills, and get students to do history by engaging students in a range of historical thinking skills, including

- Sourcing: The skill of detecting bias and judging the reliability of sources (this includes considering the intended audience, purpose, context, and point of view of a source)

- Corroboration: The skill of comparing and contrasting narratives and identifying sources to identify where points of view agree or diverge.

- Argumentation: The skill of developing claim supported by synthesizing a range of evidence

This skills-based approached also open the door to incorporate more group work, discussions, socratic seminars. There are no “right” answers in an inquiry-based classroom. Instead, there are strong arguments, conflicting evidence, and multiple points of view. Furthermore, students find value in learning skills like sourcing and corroboration. It helps them become critical and skeptical readers and thinkers. In a world where Americans read most of their news from social media, these are skills that will help students navigate a complex world.

What is an Example of Inquiry-Based Learning in Social Studies?

Inquiry-based lesson can be created from any time period or topic. All that’s needed is an essential question that has multiple right answers. For instance, on a unit of study that focuses on the Little Rock 9 and school integration, an essential question can be:

- “What was President Eisenhower’s principal motivation for using the US military to integrate Little Rock Central High”

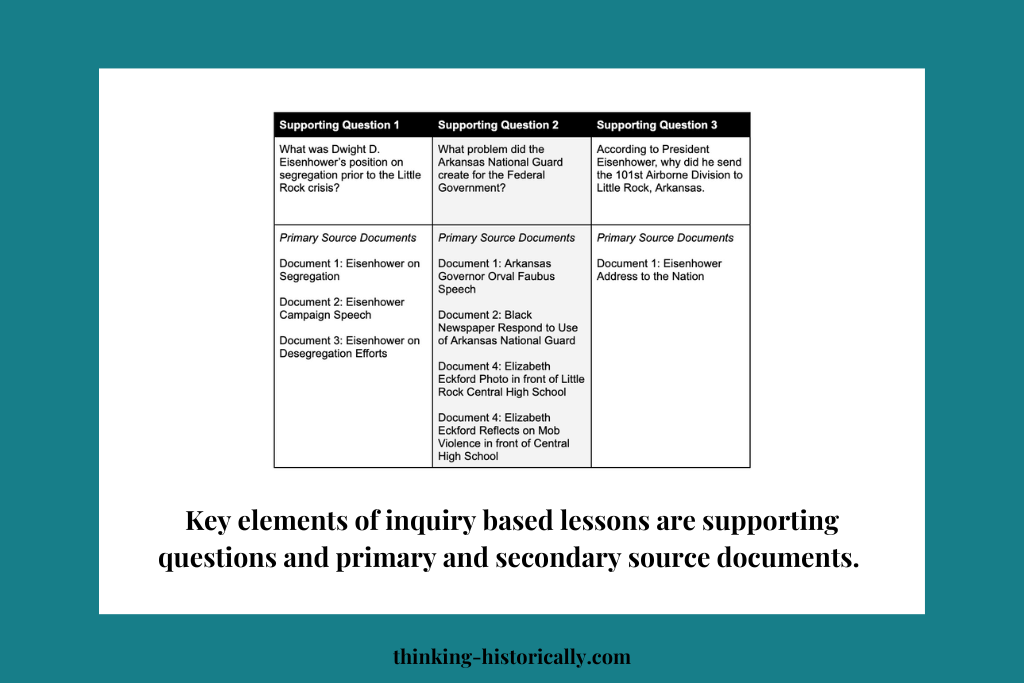

In an inquiry-based lesson, students work towards answering the essential question over the course of several lessons. During these lesson, students investigate a smaller “supporting question” by reading and analyzing 1-4 primary source documents. The primary source documents are carefully selected so students are presented with different points of view and can develop unique arguments (in this case, the documents would show that Eisenhower didn’t believe in racial equality, was concerned about America’s image during the Cold War, and wanted to assert the supremacy of the Federal government). By the end of the inquiry, student answer the essential question by creating an evidence-based argument, usually in the form of an essay. The image below illustrates the sequence of lessons and resources used to help students answer the inquiry’s essential question.

Creating Inquiry-Based Lesson Plans That Use Primary Source Documents

If inquiry-based lessons are so great, then why isn’t every teacher and their mother creating them. The answer is simple. Inquiry-based lessons are HARD to write. It seriously takes HOURS to create one inquiry-based lesson. In order to create an inquiry-based lesson you have to

- Develop an essential question that is strong enough to drive an inquiry (not all questions work)

- Design supporting questions that are coherent with the inquiry (coherence is paramount, a wrongly-worded question can cause the inquiry to lose focus and confuse students)

- Research and track down disciplinary texts/sources for work with each supporting question (this takes a long time)

- Edit/abridge text/sources into digestible excerpts that are student friendly (another time-consuming process)

Lucky for you, I’m a history nerd, and I actually find writing inquiry-based lessons enjoyable. If you want to save yourself time, consider using one of Thinking Historically’s Inquiry-Based Lessons.